It’s hard to imagine everyday life without the barcode

It’s all in the bars

Everybody knows them and everyone benefits from them. We’re talking about barcodes, a pattern of assorted lines and bars used on packages. Their impact on us and our everyday lives is enormous and we couldn’t do without them. But do you know what the very first product under a barcode scanner was? Or did you know that the “lines” started out as circles? Learn more about the development and application of barcodes and what “deadly lasers” have to do with it all.

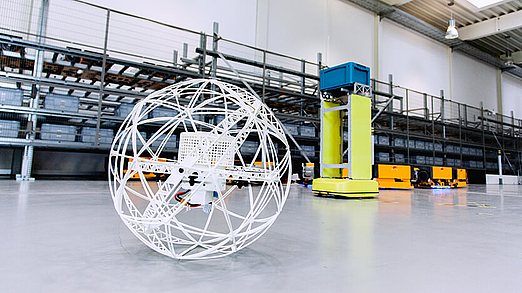

We offer specialized logistics solutions and warehousing facilities for the requirements of a range of industries.

Uniform standards in all of our logistics centers around the world ensure high quality and reliability. Benefit from our comprehensive network of warehouses in Europe, Asia and the USA.

Find out more